$ 100 as a vaccine incentive? Experiment suggests it can pay off.

What's the best way to convince the millions of Americans who are not yet vaccinated against Covid-19 to get their shots?

The reassuring public service announcements about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine have increased. But more and more people are realizing that it takes more than information to influence those who hesitate.

In recent randomized survey experiments by the U.C.L.A. The Covid-19 project for health and politics has created two seemingly strong incentives.

About a third of the unvaccinated population said paying cash would make them more likely to get a shot. This suggests that some governors are on the right track. For example, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice recently announced that the state would give young people $ 100 bonds if they were vaccinated.

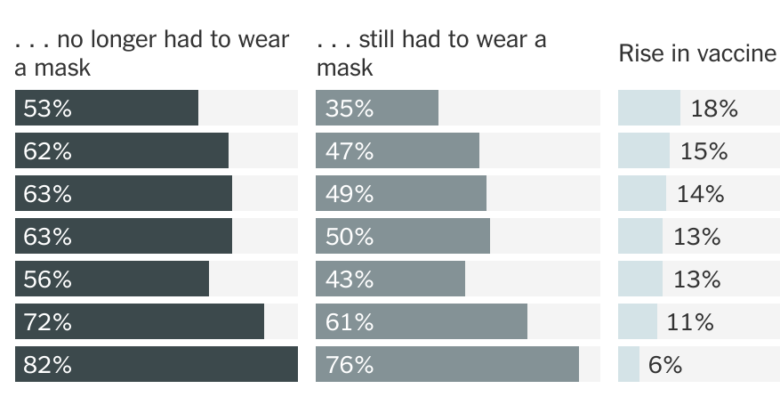

Similarly, willingness to take vaccines increased for those asked about a vaccine if it meant they did not have to wear a mask or social distance in public, compared to a group who were told they still did Do these things.

The U.C.L.A. The project, which is still ongoing, has interviewed more than 75,000 people in the past 10 months. This collaboration between doctors and social scientists at the U.C.L.A. and Harvard measures people's pandemic experiences and attitudes along political and economic dimensions, while recording their physical and mental health and wellbeing.

In order to assess the effectiveness of different messages in vaccine intake, the project randomly assigns non-vaccinated respondents to groups who see different information about the benefits of vaccination. Random assignment makes the composition of each group similar. This is important because researchers can conclude that differences between groups in people's intentions to get vaccinated are due to the messages each group saw, rather than other underlying attributes.

Last October, one group saw messages framing the benefits of vaccination in a selfish way – "It will protect you" – while others saw messages framing the benefits in a more social way: "It will protect you and those around you. “The subtle change did little; About two-thirds of the people in both groups said they intend to take the pictures.

Another experiment examined the persuasiveness of certain endorsements. Proponents included prominent figures such as then President Donald J. Trump and Dr. Anthony Fauci, but also more personal medical sources like "Your Doctor".

Most of the effects were minor. The statement by their doctor, pharmacist, or insurer that the vaccine was safe and effective had no discernible impact on vaccination intentions, although confirmation from Dr. Fauci increased the likelihood of admission by about six percentage points.

Endorsement by political figures sparked strong reactions from the partisans, with Mr Trump's endorsement decreasing acceptance among Democrats in 2020 and increasing acceptance for Republicans to a lesser extent. President Biden's approval reduced Republican acceptance in 2021. There was evidence in 2021 that Trump approval could increase Republican acceptance, but the impact was much less than when he was in office.

Updated

May 4, 2021, 6:06 p.m. ET

Last month, researchers randomly selected unvaccinated respondents to see news about financial incentives. Some people have been asked about the chances of getting a vaccine if it came with a cash payment of $ 25. other people were asked if they wanted to get $ 50 or $ 100.

About a third of the unvaccinated population said paying cash would make them more likely to get a shot. The benefits were greatest for those in the group who received $ 100, which increased willingness (34 percent said they would get vaccinated) by six points over the $ 25 group.

The effect was greatest for unvaccinated Democrats, 48 percent of whom said they were more likely to be vaccinated if provided with a $ 100 payment.

Some previous research shows that paying for vaccines can backfire, and in the U.C.L.A. Study about 15 percent of non-vaccinated people report a decline in vaccination readiness due to payments. But at this later stage in a vaccination campaign – when attention is now on hesitation – the net benefits seem to be leaning towards payment.

The incentive to stop wearing a mask and to distance oneself socially in public also had a strong result. On average, mask loosening and social distancing guidelines increased the likelihood of vaccine intake by 13 points. The Republicans saw the biggest gains, with an 18-point increase in vaccination readiness.

These results show both the difficulty of getting the remaining unvaccinated people to clinics and the promise of efforts aimed at that. While most of the messaging effects have been minor, cash payments seem to motivate the Democrats, and the relaxation of the warning guidelines seems to be working for the Republicans. (The C.D.C. recently relaxed guidelines for wearing masks outdoors for vaccinated individuals.)

The movement towards vaccinations among the reluctant may increase over time and as people observe the effects of vaccination on those who were vaccinated first. When we asked unvaccinated people why they didn't try to get a shot, 38 percent said they were concerned about the side effects and 34 percent said they didn't think the vaccine was safe. Persuasion to show that most people continue to have no side effects and that the vaccination is safe can allay these fears. Still, a quarter of those unvaccinated say they just don't trust the government's motives, and 14 percent say Covid-19 does not pose a threat to them. These people will be harder to convince.

Data from the project shows how eager Americans are to get back to normal activities. Among people who work outside of their home, 76 percent of respondents said they want to go back to the way they did before the pandemic, and 66 percent said it would be safe to do so by April. These numbers are similar regardless of vaccination status.

The April survey also asked people what social activities they had done in the past two weeks. About 30 percent said they eat in a restaurant. 17 percent said they had attended a personal religious meeting. and 11 percent met with a group of more than 10 non-family members. Almost everything took place inside.

The vaccination rates among people doing these activities largely reflect the rates in the population, which means that not everyone who is on the go has received the vaccine.

32 percent of restaurants said they were fully vaccinated (53 percent said they weren't vaccinated at all). The balance between people attending face-to-face religious gatherings was roughly the same – 41 percent said they were fully vaccinated and 41 percent said they were not vaccinated at all.

Most people at social events with more than 10 non-family members were not fully vaccinated, although the proportion of people vaccinated was higher at indoor gatherings (40 percent) than at outdoor events (27 percent).

People venture into social spaces, but around them unvaccinated people are still more numerous than vaccinated – and vaccination rates are slowing down. Reversing this trend takes more than passionate pleas from politicians, friends, or medical professionals. There may be a need to deliver real rewards beyond the health benefits of the vaccine.

Lynn Vavreck, Marvin Hoffenberg Professor of American Politics and Public Order at U.C.L.A., is a co-author of Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Struggle for the Meaning of America. Follow her on Twitter at @vavreck. She is also a lead investigator for the U.C.L.A. Covid-19 project for health and politics, together with Arash Naeim, Neil Wenger and Annette Stanton at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the U.C.L.A. and Karen Sepucha of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.