Saturated Fat: Is It Good Or Bad For You?

Saturated fat can create the dietary dilemma.

For most of your life, you have likely been told that it is unhealthy. This saturated fat clogs your arteries and leads to heart attacks.

On the other hand, type in the correct Google search terms and you will find research-based articles that say thinking is out of date and wrong.

A common claim: the idea that saturated fat is “bad” is based on bad science and is actually perfectly healthy. So healthy that you don't have to limit it. (Some say you should even eat more of it.)

There's also the following: Foods that contain saturated fat are often delicious.

You get the picture.

It is enough for you to stop in the butter section of your grocery store and be frozen indecisively. You might end up grabbing a stick, but secretly wondering if you're holding a grenade.

Like many other things we eat (carbohydrates! Red meat! Soy!), Saturated fat is … controversial.

However, in order to make educated food choices for you and your family – or, if you're a coach, helping your clients do the same – you want clarity.

Here is the truth about saturated fat.

++++

Nearly 100,000 Health and Fitness Professionals Certified

Save up to 30% on the best nutrition education program in the industry

Gain a deeper understanding of nutrition, the authority to coach it, and the ability to turn that knowledge into a thriving coaching practice.

Learn more

Why do we think saturated fat is bad?

In 1978 the seven-country study was published. This study, conducted by American physiologist Ancel Keys, found:

- a higher incidence of heart disease in countries where saturated fat consumption was high (such as the US)

- a lower incidence of heart disease in countries where saturated fat consumption was low (such as Italy, Greece and Spain)

Based on this observation, Keys hypothesized that saturated fats cause cardiovascular disease (CVD) and should be avoided. He also suggested that unsaturated fats from plants be protective and should be highlighted.

(Cool fact: these observations led to the concept of the Mediterranean diet.)

It is thanks in large part to the Seven Country Study and Ancel Keys that we have this relationship between saturated fat and heart disease.

But is it true?

Yes, but it's complicated. If you've been following us for a while, you may have noticed that nutrition science is rarely black or white.

For example, it is rare that we can say that an entire category of food is "bad" for all – or "good" for all. (More information: Why we told 100,000 customers: There is no such thing as "bad" food.)

The same applies to saturated fatty acids. While it can increase cholesterol and the risk of cardiovascular disease in some people, it doesn't in others.

And like a lot of other things, "it's the dose that makes the poison."

Excess saturated fat is not good for anyone. (However, this advice also applies to less controversial things like water, so we won't say anything interesting there.)

It's been about half a century since Keys made his observations. Since then, science has repeatedly scrutinized the truth about saturated fat.

We're telling you everything we know, including what saturated fat does in the body, what foods it comes from, and how much of it to eat.

Fette: A crash course

Before we dive into the different types of fats, let's zoom out and talk about fats in general. (If you're not ready for a biochemistry lesson, you can skip straight to the next section if you'd like.)

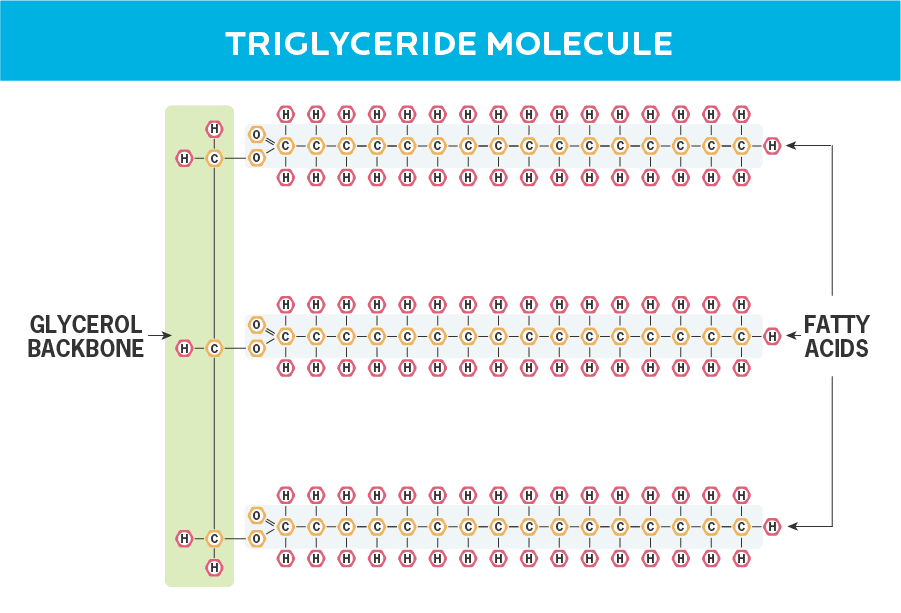

All fats are made up of fatty acids and a compound called glycerin. Fats that we eat usually have a glycerin backbone with three fatty acids attached to it. These are known as triglycerides.

To help you visualize the chemical structure of a triglyceride as you draw, it looks a lot like an uppercase "E" (the arms of the "E" are fatty acids).

See?

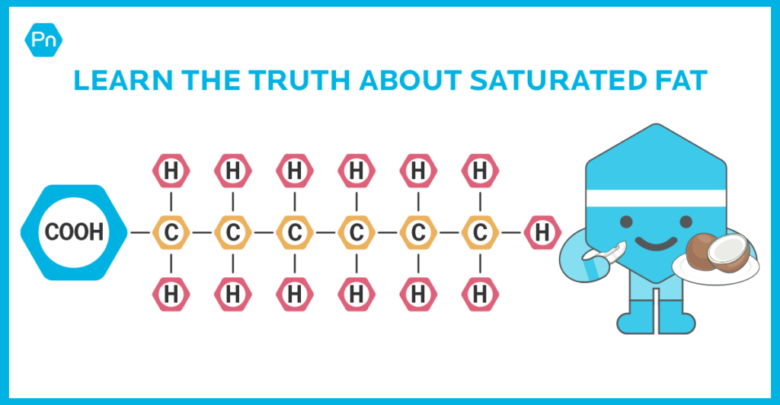

Every fatty acid consists of a "chain" of carbon atoms that are chemically linked to one another.

This "chain" can be 2 to 24 carbon atoms long. In other words, fatty acids can vary in size.

In addition, each carbon atom has two open "spots" where it can bond with up to two hydrogen atoms.

The chemical structure of a fatty acid determines how these areas are filled. (Sometimes hydrogen only fills one of the two vacancies.)

If you've had to reread this a few times – and still don't quite understand it – don't worry. For one thing, that's normal. This is abstract stuff. (We're talking about atoms!) And second, it doesn't matter.

Did you know the following: The terms "saturated", "monounsaturated" and "polyunsaturated" describe all fatty acids with slightly different chemical structures due to the nature of their bonds.

These structural differences in chemical structure lead to different functions and effects in the body.

What are saturated fats?

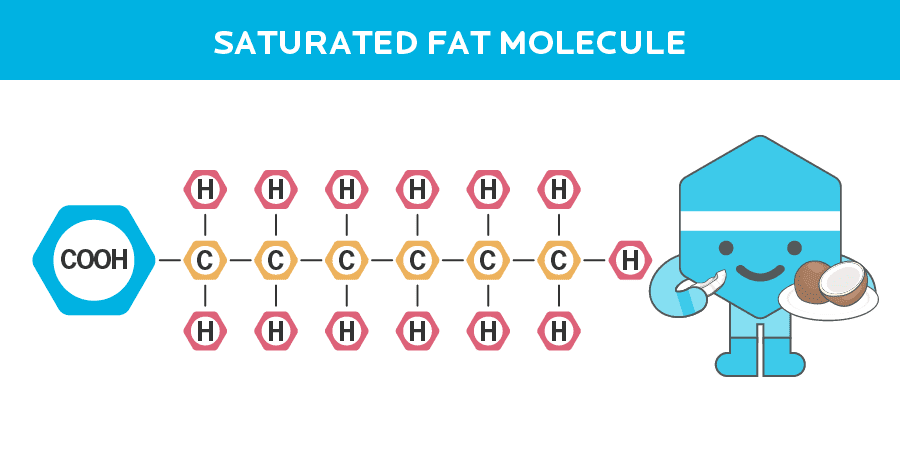

Saturated fatty acids (and fats) are called "saturated" because when you consider their chemical structure, each carbon atom forms a single bond with two hydrogen elements.

The result: your carbon chain is filled with hydrogen to capacity (saturated!). (They can no longer pass.)

Saturated fat isn't a single thing. It is actually a family of many different types of fatty acids.

Do you remember how we said that fatty acids have different chain lengths? You can have 4-carbon saturated fat, 6-carbon saturated fat, 8-carbon … you get the point.

Here are some examples of types of saturated fat (SFA):

- Butyric acid (a 4-carbon SFA produced by gut bacteria through fiber fermentation)

- Caprylic acid (an 8-carbon SFA in coconut)

- Palmitic acid (a 16-carbon SFA found in palm oil and animal fats)

- Stearic acid (an 18-carbon SFA in red meat and cocoa butter)

- Arachidic acid (a 20-carbon SFA in peanuts)

(Note: We used the common names for these fatty acids. The scientific names can be found in the table in this nerdy document courtesy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.)

Saturated Fats vs. Unsaturated Fats: What's the Difference?

Unsaturated fats include monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats.

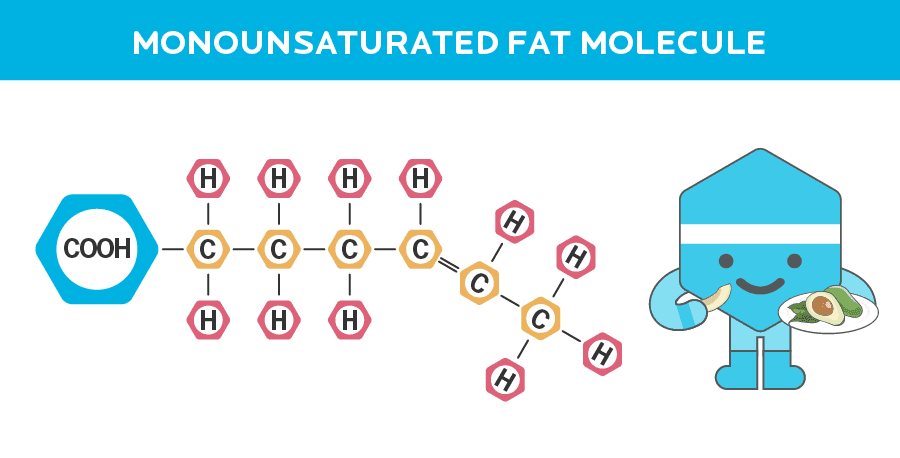

Monounsaturated fats have a double bond (hence the prefix "mono") because two places are not absorbed by hydrogen. (When two carbons have an open point, they form a double bond with each other.)

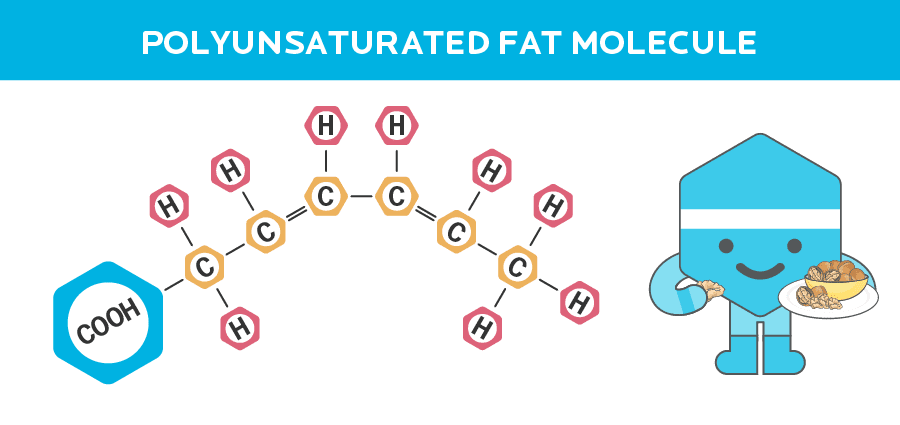

Polyunsaturated fatty acids have multiple double bonds (hence the prefix "poly") because they have multiple sites that are not taken up by hydrogen.

Here's an easy way to tell if a fat is saturated or unsaturated:

If it's solid or semi-solid at room temperature (21 ° C), it's likely saturated. (There are a few exceptions.) Think butter, coconut oil, and cocoa butter.

If it's liquid, it's very likely unsaturated. For example sunflower oil, rapeseed oil and olive oil.

This is the reason: Since unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds, their physical shape shows a "kink" or bend. They cannot pack as tightly together, which makes them "loose" and runny at room temperature.

In the meantime, saturated fats are straight and can be packed tightly together. That keeps them at room temperature.

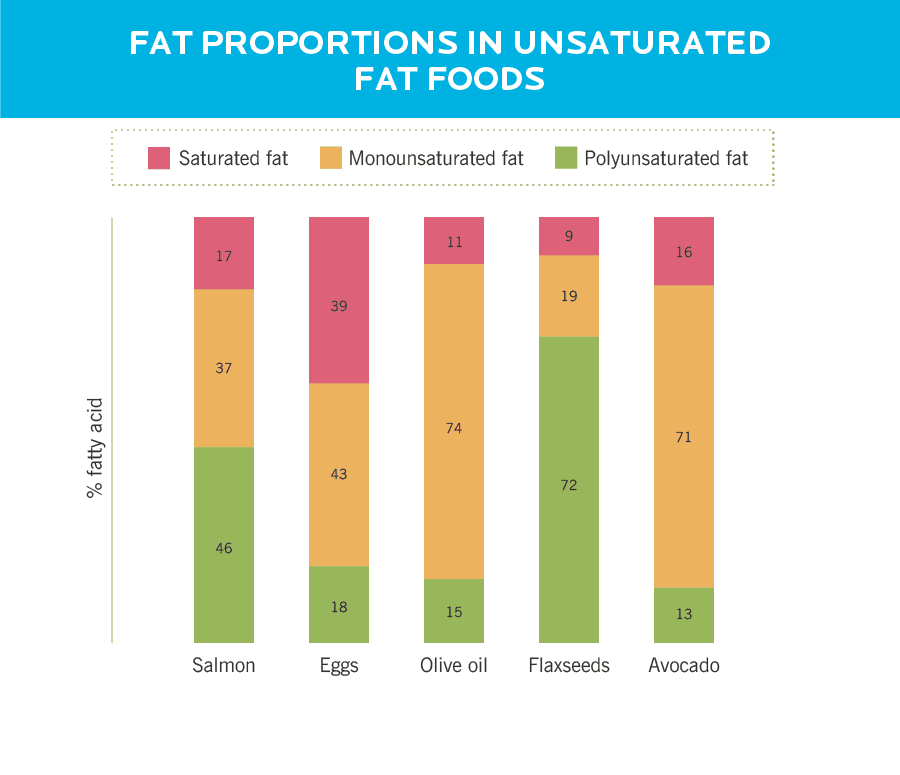

Most dietary fat sources consist of a combination of saturated, polyunsaturated, and monounsaturated fatty acids.

Trans fats: The real "bad" fat

The last type of fat is trans fats. And if there's one type of fat you want to avoid, it is this one.

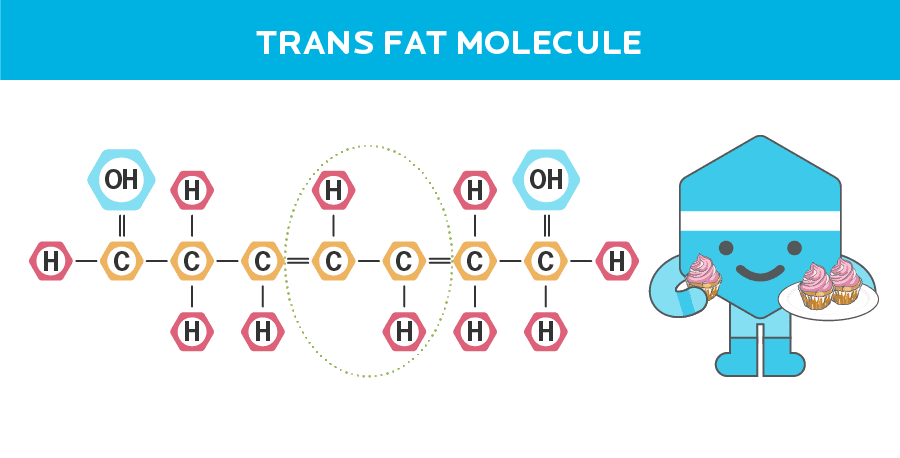

Trans fatty acids are usually the product of industrial food processing, in which polyunsaturated fats are artificially "saturated" with additional hydrogen.

As we've seen, the chemical structure of saturated fat straightens them, while the chemical structure of unsaturated fat gives them at least one bend. This shape affects their function in the body.

When unsaturated fatty acids undergo chemical hydrogenation, the fatty acids adopt a trans configuration that erects the molecule so that it looks (and acts) more like a saturated fat.

Food manufacturers like to use trans fatty acids in their products because it extends the shelf life of a food.

However, the human body doesn't handle trans fats as well.

Indeed: trans fats are directly linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, complications during pregnancy, colon cancer, diabetes, obesity and allergies.1,2,3

In fact, the FDA has determined that industrial hydrogenated fats are no longer recognized as "Generally Accepted Safe" (GRAS) and has taken steps to remove them from our food supplies

However, trans fats still exist. Vegetable fat, some margarines, some edible oils, and the processed foods and baked goods made from them all contain trans fats.

Because of this, it's still important to read the ingredient labels: Any product that says "partially hydrogenated oil" contains trans fats.

When thinking about your health, you should minimize or avoid these products as much as possible. The World Health Association (WHO) recommends that people limit their consumption of trans fats to 1 percent or less of their daily calories

Note: There are also some naturally occurring trans fats called trans fats from ruminants, such as conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and vaccenic acid (VA).

These trans fatty acids get their name because they are produced by bacteria in the stomach of ruminants such as cows, sheep and goats. In contrast to industrially produced trans fatty acids, trans fatty acids from ruminants are not associated with negative health effects

Which foods are rich in saturated fat?

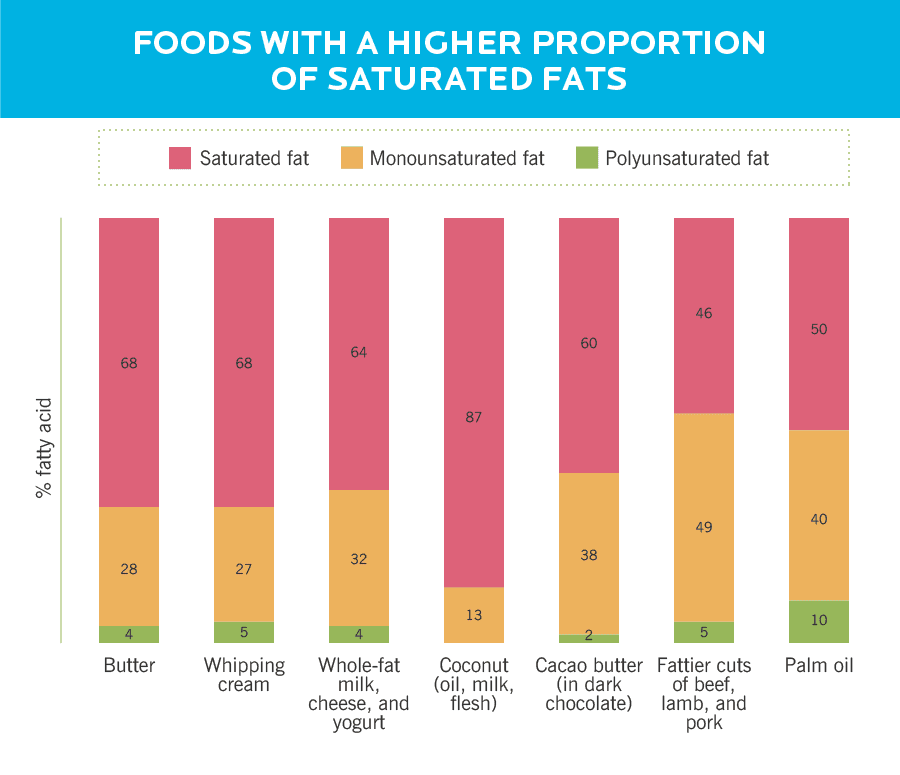

As mentioned earlier, most high fat foods are a mix of fats: saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated.

In fact, even foods that are considered "fats" are a mixture of nutrients as a whole. (For example, in addition to fats, avocado also contains carbohydrates and protein, as do walnuts and most other whole-food sources of fat.)

Foods that we call "fats" usually have fat as their predominant macronutrient. Similarly, foods we refer to as "saturated fat sources" have saturated fat as the predominant type of fat.

Food sources of saturated fat

Foods higher in saturated fat include:

- butter

- Whipped cream

- Whole milk, cheese and yogurt

- Coconut (oil, milk, meat)

- Cocoa butter (dark chocolate)

- Fatter cuts of beef, lamb and pork

- Palm oil

Foods that are higher in unsaturated fats (but still contain some saturated fats) include:

- salmon

- Eggs

- olive oil

- linseed

- avocado

- And other

Okay, but does butter kill me faster or not?

Finally, one more answer to your burning question.

Saturated fats aren't inherently bad.

A healthy diet naturally includes some saturated fats, as saturated fats are found in many healthy foods (like nuts and seeds, animal products, coconut, and avocado).

But like most foods, saturated fats are best consumed in moderation.

Here's why …

Saturated fats, cholesterol and cardiovascular disease

Those Mediterranean – those watched by Ancel Keys – may be up to something. With their diets based on vegetables, whole grains, fruits, seafood, olives, nuts, and a little dairy products, they showed remarkably low rates of heart disease.

In contrast, the Americans in this study – with their diets high in saturated fat, meat, dairy, and desserts, with fewer vegetables – had some of the highest rates of heart disease in the world.

With the help of science, we now understand these observations a little better.

Here's what we know:

▶ Excessively consumed saturated fats (over 10 percent of daily calories) increase LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) and the overall likelihood of heart attack, stroke and cardiovascular events.7,8

As the consumption of saturated fatty acids decreases, so does the risk of cardiovascular events. 8

However, saturated fats do not increase the risk of death. They also seem to have little to no effect on cancer risk, diabetes, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, or blood pressure

▶ Trans fats, on the other hand, increase both the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. 9

▶ In the meantime, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acid intake is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and death

What does it all mean?

Well it means that when it comes to fats we should do the following:

- Prioritize foods high in monoun and polyunsaturated fats, such as most nuts and seeds, seafood, olives and olive oil, and avocado.

- Moderate foods high in saturated fats, such as thicker cuts of meat, high fat dairy products and the foods made from them, palm oil, and coconut.

- Reduce or eliminate foods that are high in trans fats, such as processed foods, vegetable fat, and margarine / edible oils made with hydrogenated oils.

So should everyone just cut down on saturated fats?

Most people in western countries eat fairly high amounts of saturated fat. So many people should think about reducing their saturated fat intake.

(As far as we know, reducing saturated fat doesn't seem to have any deleterious effects.) 8

But…

Cutting down on saturated fat isn't always a good thing as it depends on what you're adding in its place.

We know that replacing some of these saturated fats with unsaturated fats can improve health if saturated fats are eaten in excess

However, when people consume fewer saturated fats and replace those calories with refined carbohydrates, the risk of a heart attack increases

Also, not all saturated fats in the saturated fat family have the same effect. For example, stearic acid, a saturated fatty acid found in beef and cocoa butter, appears to be decreasing or has no effect on LDL cholesterol. 13

The reality is this: how saturated fat affects the body is affected by many other things, such as:

- Amounts and types of other fats in the diet

- Consumption of fruits, vegetables and fiber

- Excess calories

- Training frequency and intensity

- Stress and Management

- genetics

And more.

So it's complicated.

Based on the abundance of evidence, it seems that we want to consider two things when it comes to keeping dietary fats within a healthy range:

- Amount: Not too much and not too little. About 30 percent of your daily calories should come from different types of fat (saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated).

- Ratio: Aim for roughly equal proportions of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats.

Numbers aside, the takeaway message is if you are eating a fairly balanced whole foods diet and not consuming excess calories, you probably don't have to worry too much about your saturated fat intake.

But you probably shouldn't intentionally increase your saturated fat intake either for so-called "therapeutic" effects (example: the butter coffee trend).

This means that saturated fats fall directly into the “enjoy in moderation” category.

How Much Saturated Fat Should I Eat?

As always, the answer is: it depends.

A good general guideline, however, is that saturated fats should make up about 10 percent or less of total daily calories. 14

This means that a 2,000 calorie sample can contain approximately 200 calories – or approximately 22.2 grams – that come from saturated fat. (Adjust it up or down to suit your specific energy needs.)

Here are some examples of what this might look like:

- 7 ounces sirloin steak = 12 grams of saturated fat

- 1 ounce of cheddar cheese = 6 grams of saturated fat

- 3 large eggs = 5 grams of saturated fat

= 23 grams of saturated fat

Or:

- 6 ounces of salmon = 5 grams of saturated fat

- 1 tablespoon of coconut oil = 12 grams of saturated fat

- 1 avocado = 4 grams of saturated fat

= 21 grams of saturated fat

As you can see, getting that 10 percent is easy.

It's also easy to go beyond 10 percent, especially if thicker cuts of meat and cooking fats like butter, coconut, or palm oil are regularly included in your diet.

However, if along with these saturated fat sources you also …

- A good balance of unsaturated fats (from extra virgin olive oil, nuts and seeds)

- Appropriate protein, carbohydrates and colorful fruits and vegetables from a variety of minimally processed whole foods (more information: "What foods should I eat?")

- Daily exercise from stretching, walking, strength training, dancing, old-fashioned butter stirring

… you probably don't have to worry about saturated fat.

If you want to find out exactly how much fat – and carbohydrates, protein and vegetables – your body (or your client's) needs for your preferred eating style, check out our fantastic nutrition calculator.

Our comprehensive advice for your day-to-day life: Don't get too caught up (or overwhelmed) by the numbers.

Instead, focus on the following four points.

1. Get a mix of fats.

Man developed a varied and seasonal diet. We live best on a mixture of fat types – in relatively equal balance – from different types of food.

This balance naturally arises when we choose a wide variety of different whole, minimally processed foods that contain fat, such as:

- Nuts and seeds

- Avocados

- dairy

- Eggs

- oily fish

- Beef, pork and lamb

- poultry

- wild game

- Olives and extra virgin olive oil

Add one or two of the above sources of fat to each meal and you will likely meet your fat needs.

2. Avoid trans fats.

Try to minimize or eliminate refined and processed foods that contain manufactured fats and artificially hydrogenated fats (read: trans fats).

This happens naturally the more you focus your diet on whole foods. (Learn How: The 5 Principles of Good Diet.)

3. Look at the whole person.

Most importantly, tailor your saturated fat intake to suit your (or your clients') unique body, preferences and needs.

People with cholesterol or cardiovascular problems in their families may be more (genetically) sensitive to the negative effects of saturated fats and should therefore limit their consumption.

However, sometimes it is appropriate to eat slightly higher amounts of saturated fat. For example:

- Larger, more muscular, and more active people can generally eat proportionally more, including more saturated fats. However, it is still a good idea to keep saturated fats in the 10 percent range of total daily calories.

- If having croissants, dark chocolate, and coffee with cream is important to you or your customer, don't "forbid" it. Moderate it, understand the tradeoffs, and enjoy it.

- Some people feel comfortable on a high-fat diet. It may be appropriate for these people to eat more fats, including saturated fats. However, if saturated fats are a major source of calories, then you should work with your doctor to regularly test your cholesterol and blood lipids to make sure they are in a normal range.

4. When in doubt (but still curious): experiment.

Above we suggested limiting saturated fat consumption to around 10 percent of total daily calories.

This is a good, conservative recommendation for most people, especially if you have a family history of high cholesterol or cardiovascular disease.

But what if you want to try a higher fat diet – like the keto diet – and increase your overall fat intake?

Try it out.

To do so so that you know whether or not this type of diet will work for you, just adopt this mindset: think like a scientist.

Decide What Result You Are Looking For When Trying A Higher Fat Diet: Reduced Desire? Fat loss? Better energy? (Read More: 3 Diet Experiments That Can Change Your Eating Habits And Transform Your Body)

Then take some baseline measurements:

- Weight, girth, photos

- Energy level, sleep quality, digestion, mood (you can easily measure these on a scale from 1 to 10)

- Cholesterol (LDL, HDL, and Total), Triglycerides, Fasting Blood Sugar (work with your doctor to get and interpret these measurements)

- Anything else you want to track, like food cravings or satisfaction with food.

Next, start your experiment: increase your fat consumption.

Check in every week or two to evaluate (most of) the measurements above. (If you work with a doctor to check cholesterol and other blood markers, repeat a blood test after about three months.)

If you are fine, move on. Every few months, evaluate how you are overall.

Feeling better and looking better? Avocado and coconut shakes still tasty? Blood tests get a thumbs up from Doc? Cool! Go ahead and reevaluate in about another six months. (To quickly and easily see how your diet is working for you, try ours Best diet quiz.)

Feeling crappy and blood lipids creeping up on you? All right. Cut down on the fat – especially the saturated fat.

Tinker about things until you (and your doctor) are happy.

Ignore the marketing claims for butter coffee – as well as celery juice – and see what your own body is saying.

Most likely, this stick of butter isn't a grenade. It is also not a golden elixir of health.

It's just butter.

References

Click here to view the sources of information referenced in this article.

1. Oteng, Antwi-Boasiako and Sander Kersten. 2020. "Mechanisms of Action of Trans Fatty Acids." Advances In Diet 11 (3): 697-708.

2. Souza, Russell J. de, Andrew Mente, Adriana Maroleanu, Adrian I. Cozma, Vanessa Ha, Teruko Kishibe, Elizabeth Uleryk et al. 2015. "Ingestion of Saturated and Trans-Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Risk of All-Causes Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies." BMJ 351 (August): h3978.

3. Dhaka, Vandana, Neelam Gulia, Kulveer Singh Ahlawat and Bhupender Singh Khatkar. 2011. "Trans Fat Sources, Health Risks, and Alternative Approach – A Review." Journal of Food Science and Technology 48 (5): 534-41.

4. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. n.d. "Trans fat." Accessed January 13, 2021.

5. "Diet: Trans Fat." n.d. Accessed January 13, 2021.

6. Gebauer, Sarah K., Jean-Michel Chardigny, Marianne Uhre Jakobsen, Benoît Lamarche, Adam L. Lock, Spencer D. Proctor and David J. Baer. 2011. "Effects of Ruminant Trans Fats on Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Epidemiological, Clinical, and Mechanistic Studies." Advances in Diet 2 (4): 332–54.

7th "WHO | Effects of saturated fat on serum lipids and lipoproteins: a systematic review and regression analysis. " 2016, August.

8. Hooper, Lee, Nicole Martin, Oluseyi F. Jimoh, Christian Kirk, Eve Foster, and Asmaa S. Abdelhamid. 2020. "Reducing Saturated Fat Intake in Cardiovascular Disease." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8 (August): CD011737.

9. Zhuang, Pan, Yu Zhang, Wei He, Xiaoqian Chen, Jingnan Chen, Lilin He, Lei Mao, Fei Wu, and Jingjing Jiao. 2019. "Dietary fats in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort of 521,120 people with 16 years of follow-up." Circulation Research 124 (5): 757-68.

10. Guasch-Ferré, Marta, Nancy Babio, Miguel A. Martínez-González, Dolores Corella, Emilio Ros, Sandra Martín-Peláez, Ramon Estruch et al. 2015. "Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a population at high risk for cardiovascular disease." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 102 (6): 1563-73.

11. Wang, Dong D., Yanping Li, Stephanie E. Chiuve, Meir J. Stampfer, Joann E. Manson, Eric B. Rimm, Walter C. Willett, and Frank B. Hu. 2016. "Association of Specific Dietary Fats with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality." JAMA Internal Medicine 176 (8): 1134-45.

12. Jakobsen, Marianne U., Claus Dethlefsen, Albert M. Joensen, Jakob Stegger, Anne Tjønneland, Erik B. Schmidt and Kim Overvad. 2010. "Carbohydrate Intake Versus Saturated Fat Intake and Myocardial Infarction Risk: Importance of the Glycemic Index." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 91 (6): 1764-68.

13. Jesch, Elliot D. and Timothy P. Carr. 2017. "Food Ingredients That Reduce Cholesterol Absorption." Preventive Nutrition and Food Science 22 (2): 67–80.

14. Liu, Ann G., Nikki A. Ford, Frank B. Hu, Kathleen M. Zelman, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Penny M. Kris-Etherton. 2017. "A Healthy Approach to Dietary Fats: Understanding the Science and Taking Actions to Reduce Consumer Confusion." Nutrition Journal 16 (1): 53.

If you are or want to be a trainer …

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes – in ways that are tailored to their unique bodies, preferences, and circumstances – is both an art and a science.

If you want to learn more about both of them, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 certification. The next group will start shortly.