PCOS: 3 Evidence-Based Strategies That Really Work.

Reviewed by Stephanie Paver, MS, RD

What is PCOS | Causes | Symptoms | PCOS diet | Treatment | Weight loss | For trainers

Acne, hair in weird places, weight gain, irregular periods, and fertility problems.

These are just a few of the symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal problem that affects up to 20 percent of women worldwide

Because of the diversity of symptoms and the lack of a clear diagnostic test, some women have to wait years – and see multiple health professionals – before getting an accurate diagnosis

Even with good advice, women with PCOS can have difficulty doing what they know is good for them:

▶ When fatigue is an issue, exercise can feel as appealing as dragging garbage on a hot day.

▶ When sleep is elusive, appetite can increase, making processed foods seem even more irresistible.

▶ When mental health suffers, everything can seem more difficult.

Also frustrating: Trying to find consistent, evidence-based PCOS advice online. Serious. Pooh.

This is why we wrote this article so that trainers and people with PCOS can find trusted advice that actually works.

++++

Above 150,000 certified health and fitness professionals

Save up to 30% on the best nutrition education program in the industry

You will gain a deeper understanding of nutrition, the authority to coach it, and the ability to translate that knowledge into a successful coaching practice.

Learn more

What is Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)?

Doctors diagnose PCOS when someone has at least two of the following symptoms:

✓ Irregular periods: They can be shorter than 21 days, longer than 35 days or completely absent.

✓ "Cysts" in the ovaries: confirmed by ultrasound, these growths are not real cysts, but a collection of egg follicles.

✓ High levels of androgens, such as testosterone: This is confirmed by a blood test or visible signs such as facial hair, acne, or male pattern baldness.

Although not a diagnostic criterion, high levels of insulin and a decreased ability to tolerate carbohydrates are also common.

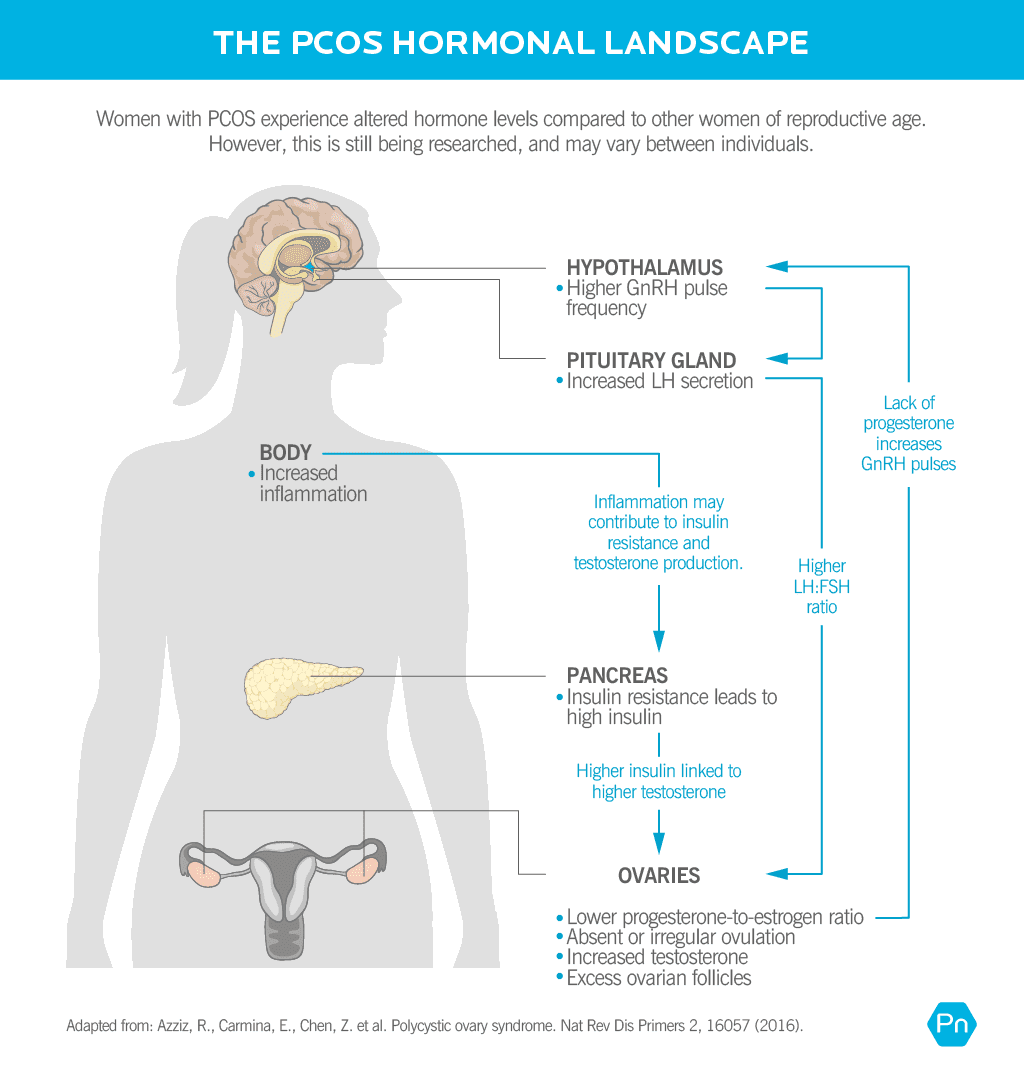

Biology lesson: the PCOS hormone cascade

PCOS probably originates from the hypothalamus, a small region in the brain that is responsible, among other things, for regulating hormones.

During a normal menstrual cycle, the hypothalamus releases a hormone called gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in regular pulses, which causes the pituitary gland to release two more hormones:

- Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

- luteinizing hormone (LH)

FSH and LH travel to the ovary and trigger the release of estrogens, androgens, and progesterones. The right proportions of these hormones stimulate ovulation, or the release of an egg.

In PCOS, the hypothalamus releases GnRH at a higher rate.

Faster and longer GnRH pulses disrupt the normal relationship between LH and FSH. Many (if not all) women with PCOS have higher levels of LH. More LH triggers the production of more androgens – like testosterone – and inhibits ovulation.

High levels of insulin – a common characteristic of PCOS – can further contribute to androgen production, as well as lowering another hormone called sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), which can lead to even higher levels of circulating free testosterone.

Women can also have dysregulated thyroid and adrenal function.

Just like the ovaries, the thyroid and adrenal glands are dependent on normal hypothalamus and pituitary function.

It is this hormonal circus that causes the amount of symptoms that appear in different systems of the body.

What causes PCOS?

PCOS arises from a combination of four main influences.

genetics

Multiple genes contribute to an increased risk of PCOS, although carrying a particular variant of the gene doesn't guarantee you will show symptoms.4, 5, 6

The fetal environment

If your mother has higher testosterone levels with you during pregnancy, your risk of developing PCOS increases. 7, 8

Childhood trauma

Chronic stress in early life can lead to changes in the brain that alter hormone regulation and increase the risk of many diseases such as immune, metabolic, cardiovascular and psychiatric disorders

Women with PCOS were twice as likely to experience childhood trauma. 11

Lifestyle habits

Sedentary lifestyles, poor diet, and obesity all contribute to insulin resistance and excessive inflammation.

This makes PCOS more likely and makes symptoms worse.

Getting enough exercise, eating well, and weight management won't cure you if you have PCOS, but they can improve symptoms, quality of life, and future health outcomes

Several environmental pollutants have also been linked to PCOS. 13

These include brominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, perfluorinated compounds, phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA). These chemicals are important hormone disruptors and are found in air, water, soil, and food, as well as in household cleaners, food containers, and beauty products.

PCOS symptoms

Hormonal imbalances create a constellation of symptoms that vary from person to person and range from very mild to severe.

▶ Menstrual disorders: the period can not only be longer or shorter than usual, it can also be very heavy or very light.

▶ Infertility / Anovulation: High levels of androgens stop the release of an egg and inhibit ovulation.

▶ Ovarian “cysts” / follicles: Many – but not all – women with PCOS have an accumulation of immature ovarian follicles (often incorrectly called “cysts”).

▶ Changes in hair growth: High androgen levels can cause coarse hair to develop on the face, chest, stomach, or back, a symptom known as hirsutism. In the meantime, hair on the parting and the front of the head can become thinner.

▶ Weight gain and / or persistent weight loss: Weight can hang like a persistent barnacle, possibly due to the combination of high androgens, high blood sugar and insulin, unregulated inflammation, and / or a sluggish thyroid.

▶ Acne: High androgen and insulin levels can contribute to oily skin and stubborn acne – especially in the chin area, but also on other areas of the face, back or chest. Painful, longer-lasting cysts can also appear around the armpits, under the breasts, or around the groin, a condition called hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa.

▶ Dark patches of skin: Also known as acanthosis nigricans, high insulin levels can cause dark, thickened, velvety skin in the folds of the body, especially around the armpits, neck and groin.

▶ Low energy and carbohydrate cravings: Some women with PCOS have a reduced ability to tolerate processed carbohydrates. Translation: 15 minutes after you ate this scone, you dozed off and your face adapts to your keyboard.

▶ Increased risk of diabetes: Compared to the general population, women with untreated PCOS are more than four times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes and almost three times more likely to develop gestational diabetes. 14

▶ Blood lipid imbalance: high blood sugar and insulin can contribute to low levels of high-density lipoproteins (the “good” cholesterol), high triglycerides and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

▶ Sleep problems: PCOS is associated with sleep apnea, i. H. if breathing stops regularly during sleep. 15

▶ Mood swings, anxiety, and depression: PCOS can increase the likelihood of mood swings, anxiety, and depression.16 Since many women with PCOS struggle with their weight, they are also at an increased risk of eating disorders.

Both the visible and invisible symptoms of PCOS can be incredibly distressing and affect self-esteem.

Fortunately, there is help.

PCOS and Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Women with Hashimoto's thyroiditis – an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland – are more than three times more likely to develop PCOS than the general population.17, 18

Why are the two related? It is still unclear.

What we know:

- Both PCOS and Hashimoto's thyroiditis have a strong genetic component. A handful of genes (FBN, GNRHR, and CYP1B1) have been linked to both, although researchers are unsure whether these genes fully explain their association.19

- Women with PCOS have higher estrogen-to-progesterone ratios, which can increase immune activity. This is bad news for autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto, which are characterized by an already overactive immune system.

- Women with PCOS may have less gut microbiome diversity.20, 21 This can further impair the immune system.

This landscape is like adding gasoline to an autoimmune fire, increasing the likelihood of Hashimoto's. 22

PCOS treatment

You can find PCOS treatment plans out there on the internet listing dozens of "never-eat" foods and fitness programs that will sweat until you drop.

You won't find that here. From our experience with over 100,000 customers, we know one thing for sure: It takes a rare person to consistently stick to an extreme diet and fitness plan.

The good news: Most people see massive improvements with just three tiny and much more realistic lifestyle changes.

The PCOS Diet: Be Smart With Carbohydrates

You probably don't (and shouldn't) need to cut carbohydrates altogether to control energy and blood sugar, but some research shows that a low-carb – and possibly low-milk – diet can help

The advice

Focus on what you want to eat instead of what you shouldn't be eating. Aim for around 10 grams of fiber and 20-30 grams of protein (roughly a palm-sized serving) per meal by building plates around these nutrient-dense foods.

- Lean proteins: meat and poultry, fish and shellfish, eggs, tofu, and tempeh

- Colorful, non-starchy vegetables: cruciferous vegetables (think broccoli, cabbage, and kale), lettuce, cucumber, celery, summer squash, tomatoes, mushrooms, peppers, and asparagus

- Low-sugar fruits: berries, apples, oranges and plums

- Healthy fats: avocado, olives, nuts and seeds, and oils (olive and coconut)

Fill your plate with smaller amounts of dairy products, starchy vegetables, or whole grains as the above products take up most of the space.

To make more nutritious food choices, check out this visual guide: "What should I eat ?!"

For more precise nutritional recommendations tailored to your body, lifestyle, and goals – including portion recommendations for the above food groups – see: The Precision Nutrition Calculator.

Are There Diet Supplements That Help PCOS?

Below is a list of the most effective, evidence-based supplements used to treat PCOS.

If you're a coach, encourage your client to speak to their doctor first.

| nutrient | Mechanism of action | Evidence level | Recommended dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inositol | Helps regulate hormone levels and the menstrual cycle, as well as improving insulin sensitivity, egg quality and fertility. 24, 25, 26 | Very high | Two forms are most effective: myo-inositol (4,000 mg / day) and D-chiro-inositol (100 mg / day) |

| zinc | Zinc deficiency is more common in women with PCOS27 and supplementation can regulate hair growth and improve skin quality.28 | Moderate | 30-50 mg / day for 8 weeks, with a meal (may cause nausea on an empty stomach) |

| Vitamin D | Plays a role in ovarian follicle development and progesterone production, both important in maintaining a healthy menstrual cycle and fertility. 29 | Moderate | If a blood test confirms a deficiency, 1,000 to 2,000 IU / day can help normalize levels |

| magnesium | Helps regulate blood sugar, estrogen and progesterone production and supports the nervous system. | Moderate | 200-400 mg / day |

| chrome | Improves insulin sensitivity and may help lower high blood sugar. 30 | Moderate | 200-1,000 µg / day (in the higher range, separate doses in two or more) |

PCOS Exercise: Find Joyful Movement

Most beings benefit from regular exercise. (Even pet hamsters are happier with an exercise bike in their cage.)

In women with PCOS, exercise can:

- Improve ovulation and menstrual regularity31

- Improve insulin sensitivity

- Lower androgens

- Reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease

- Improve mental health32, 33

These advantages show up with or without additional dietary changes and regardless of weight changes. Intentional meaning: Exercise is a superpowered tool.

The advice

Aim for at least 120 minutes of moderate exercise per week.34 This equates to about four 30-minute units, with half of these units (ideally) devoted to strength training.

But start wherever you are.

▶ If you go to the gym regularly, stay tuned. Resistance training can be especially beneficial as it helps improve insulin sensitivity and the ratio of fat to lean mass.35 (Plus, lifting heavy things feels badass.)

▶ If your main activity is running errands, e. B. Carrying your groceries or going to the bus stop, try adding a little more. Consider following your steps to get a baseline, then set a goal for a higher number. Or add an online or classroom course or training once or twice a week. (For a 10-minute workout without equipment, see: How to Stay in Shape When You're Busy.)

▶ If the word “exercise” makes you want to wash your mouth with soap, just start somewhere. A five-minute walk or a dance party also counts. (Wiggling your finger and saying "Nuh-uh" doesn't work. Nice try.)

Most importantly, find something that you really enjoy because you're more likely to stick with it.

Choose the exercise variant that suits you best. When you feel comfortable and consistent with more exercise, reevaluate and add a little more if that suits your skills and goals.

PCOS: two different types?

Women with PCOS can have slightly different hormone profiles (and symptoms) depending on whether they also have excess body fat. In recognition of the two subpopulations, experts use these terms36:

- The reproductive type (sometimes referred to as “lean PCOS”) tends to have a lower BMI and lower insulin resistance, but higher luteinizing hormone (LH) and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) .37

- Metabolic type tends to have higher BMI, more glucose and insulin dysregulation, and lower LH and SHBG levels.

With the exception of weight loss, the lifestyle recommendations we suggest in this article still apply to both groups.

Stress management: self-love is the new cool

With PCOS, it can be easy to fall into self-criticism and pessimistic thinking. So when you do your best to make healthy changes in your life, you also bring an abundance of self-compassion with you.

The advice

Pay attention to your thoughts, and if you find yourself being rude or overly critical, practice talking to yourself as you would to your best friend.

Acknowledge that your condition can be a real struggle at times.

And while it is not your fault, it is your responsibility to take care of yourself as well and kindly as possible.

It can be helpful to remember that many other women are also dealing with PCOS. It can be helpful to join a PCOS support group or just to think about the other women who are “with you”.

In addition to having a self-compassionate mindset, make sure you prioritize these stress-relieving basics.

▶ Get enough sleep. A good night's sleep helps balance hormones and mood, makes it easier to regulate weight and appetite, and makes Tiredzilla less likely to torment your friends and family. (For tips on how to improve sleep, see: The Power of Sleep.)

▶ Include daily stress-relieving activities. Meditation, nature walks, spending time with loved ones, and creative hobbies are stress-relieving superstars. For even more stress relief, read: Do you feel like you are failing at self-sufficiency? 3 solutions that can actually help.

▶ Think about how you are going to make your PCOS story. Are you a helpless PCOS victim? Or can PCOS be an opportunity to learn more about your health and take better care of yourself? Which story feels better? Which story motivates you to act in a strengthening manner?

Of course you can sometimes “do everything right” and still feel completely overwhelmed, maybe even hopeless. If that's the case, get in touch. Talk to someone you know, your doctor, or a psychiatrist.

Sometimes just knowing that someone else is on your team can make the difference between “I'm in a black hole and can't get out” and “I see some light at the end of the tunnel”.

PCOS and weight loss

The truth is, it can be harder to lose weight when you have PCOS.

This is one reason why it is better to focus on the lifestyle habits that we mentioned in the previous section. Because what you eat and how you move has a bigger impact on your health and symptoms than your weight on the scales.

In many cases, fat loss occurs as a natural side effect of better overall health. But if you don't, you will still eat, move, feel, and live better better.

Advice to coaches

As a coach, it feels easy to feel outside of your realm and ask yourself, "Am I really qualified to help someone with PCOS?"

And while trainers can't diagnose or treat PCOS, you can absolutely support them – no special certifications are required.

Remember: Your client will likely have access to health professionals who are aware of the latest PCOS research and treatments.

What your client is missing in life: someone to help them put their doctor's recommendations into action.

Most likely, your doctor will recommend strategies that are pretty similar to the strategies you've used with other clients: exercise, eating healthy, and reducing stress, all of which can greatly improve symptoms of PCOS.

Stay within your limits and be the best cheerleader you can.

References

Click here to view the resources referenced in this article.

1. Deswal, Ritu, Vinay Narwal, Amita Dang and Chandra S. Pundir. 2020. "The Prevalence of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Brief Systematic Review." Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 13 (4): 261-71.

2. Sirmans, Susan M., and Kristen A. Pate. 2013. "Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." Clinical Epidemiology 6 (December): 1–13.

3. Tomlinson, Julie A., Jonathan H. Pinkney, Phil Evans, Ann Millward, and Elizabeth Stenhouse. 2013. "Screening for Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disorders in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research: Official Journal of the International Society of Diabetes and Vascular Disease 13 (3): 115-23.

4. Crespo, Raiane P, Tania A.S. S. Bachega, Berenice B. Mendonça, and Larissa G. Gomes. 2018. "An Update on the Genetic Basis of PCOS Pathogenesis." Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism 62 (3): 352-61.

5. Dunaif, Andrea. 2016. "Perspectives in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: From Hair to Eternity." The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 101 (3): 759-68.

6. Vink, J.M., S. Sadrzadeh, C.B. Lambalk, and D.I. Boomsma. 2006. "Inheritance of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome in a Dutch Twin Family Study." The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91 (6): 2100-2104.

7. Dumesic, Daniel A., David H. Abbott, and Vasantha Padmanabhan. 2007. "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Its Developmental Origins." Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 8 (2): 127–41.

8. Tata, Brooke, Nour El Houda Mimouni, Anne-Laure Barbotin, Samuel A. Malone, Anne Loyens, Pascal Pigny, Didier Dewailly et al. 2018. "Elevated prenatal anti-Müllerian hormone reprograms the fetus and induces polycystic ovarian syndrome in adulthood." Natural Medicine 24 (6): 834-46.

9. Kuras, Yuliya I., Naomi Assaf, Myriam V. Thoma, Danielle Gianferante, Luke Hanlin, Xuejie Chen, Alexander Fiksdal and Nicolas Rohleder. 2017. "Dulled daily cortisol activity in healthy adults with childhood adversity." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 11 (November): 574.

10. Felitti, V.J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. P. Koss, and J.S. Marks. 1998. “Relationship of Child Abuse and Household Disorders to Many of the Leading Causes of Adult Death. The Study of Unwanted Childhood Experiences (ACE). American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14 (4): 245-58.

11. Tay, Chau Thien, Helena J. Teede, Deborah Loxton, Jayashri Kulkarni, and Anju E. Joham. 2020. "Psychiatric Comorbidities and Adverse Childhood Experiences in Women with Self-Reported Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: An Australian Population-Based Study." Psychoneuroendocrinology 116 (June): 104678.

12. Merkin, Sharon Stein, Jennifer L. Phy, Cynthia K. Sites, and Dongzi Yang. 2016. "Environmental Determinants of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." Fertility and Sterility 106 (1): 16-24.

13. Vagi, Sara J., Eduardo Azziz-Baumgartner, Andreas Sjödin, Antonia M. Calafat, Daniel Dumesic, Leonardo Gonzalez, Kayoko Kato, Manori J. Silva, Xiaoyun Ye and Ricardo Azziz. 2014. "Investigating the Potential Association Between Brominated Diphenyl Ethers, Polychlorinated Biphenyls, Organochlorine Pesticides, Perfluorinated Compounds, Phthalates, and Bisphenol A in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Case-Control Study." Endocrine Disorders of the BMC 14 (October): 86.

14. Joham, A. E., S. Ranasinha, S. Zoungas, L. Moran, and H. J. Teede. 2014. "Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in women of childbearing age with polycystic ovarian syndrome." The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 99 (3): E447-52.

15. Ehrmann, David A. 2012. “Metabolic Disorder in PCOS: Association with Obstructive Sleep Apnea.” Steroids 77 (4): 290–94.

16. Zehravi, Mehrukh, Mudasir Maqbool and Irfat Ara. 2021. "Depression and Anxiety in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Review of the Literature." International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, August. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2021-0092.

17. Kowalczyk, K., G. Franik, D. Kowalczyk, D. Pluta,. Blukacz and P. Madej. 2017. "Thyroid Disorders in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 21 (2): 346-60.

18. Ulrich, Jan, Julia Görges, Christoph Keck, Dirk Müller-Wieland, Sven Diederich and Onno Eilard Janssen. 2018. "Effects of Autoimmune Thyroiditis on Reproductive and Metabolic Parameters in Patients with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes: Official Journal of the German Society for Endocrinology (and) the German Diabetes Society 126 (4): 198–204.

19. Gaberšček, Simona, Katja Zaletel, Verena Schwetz, Thomas Pieber, Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch and Elisabeth Lerchbaum. 2015. "Mechanisms in Endocrinology: Thyroid and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." European Journal of Endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies 172 (1): R9-21.

20. Wang, Lan, Jing Zhou, Hans-Jürgen Gober, Wing Ting Leung, Zengshu Huang, Xinyao Pan, Chuyu Li, Na Zhang and Ling Wang. 2021. "Changes in the gut microbiome associated with PCOS affect clinical phenotype." Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 133 (January): 110958.

21. Lindheim, Lisa, Mina Bashir, Julia Münzker, Christian Trummer, Verena Zachhuber, Bettina Leber, Angela Horvath and others. 2017. "Changes in Gut Microbiome Composition and Barrier Function Associated with Reproductive and Metabolic Defects in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS): A Pilot Study." PloS One 12 (1): e0168390.

22. Arduc, Ayse, Bercem Aycicek Dogan, Sevgi Bilmez, Narin Imga Nasiroglu, Mazhar Muslum Tunfisch, Serhat Isik, Dilek Berker and Serdar Guler. 2015. "High prevalence of Hashimoto's thyroiditis in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: Does the imbalance between estradiol and progesterone play a role?" Endocrine Research 40 (4): 204-10.

23. Phy, Jennifer L., Ali M. Pohlmeier, Jamie A. Cooper, Phillip Watkins, Julian Spallholz, Kitty S. Harris, Abbey B. Berenson, and Mallory Boylan. 2015. "A low-starch / low-milk diet leads to successful treatment of obesity and comorbidities associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)." Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Therapy 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7904.1000259.

24. Monastra, Giovanni, Vittorio Unfer, Abdel Halim Harrath and Mariano Bizzarri. 2017. "The combination of treatment with Myo-Inositol and D-Chiro-Inositol (40: 1) is effective in restoring ovarian function and metabolic balance in PCOS patients." Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society for Gynecological Endocrinology 33 (1): 1-9.

25. Kamenov, Zdravko and Antoaneta Gateva. 2020. "Inositols in PCOS." Molecules 25 (23). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25235566.

26. Laganà, Antonio Simone, Simone Garzon, Jvan Casarin, Massimo Franchi and Fabio Ghezzi. 2018. "Inositol in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Restoring Fertility through a Pathophysiological Approach." Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 29 (11): 768-80.

27. Abedini, Maryam, Ehsan Ghaedi, Amir Hadi, Hamed Mohammadi and Reza Amani. 2019. "Zinc Status and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology: Organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements 52 (March): 216-21.

28. Jamilian, Mehri, Fatemeh Foroozanfard, Fereshteh Bahmani, Rezvan Talaee, Mahshid Monavari, and Zatollah Asemi. 2016. "Effects of zinc supplementation on endocrine outcomes in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study." Biological trace element research 170 (2): 271-78.

29. Lin, Ming-Wei, and Meng-Hsing Wu. 2015. "The Role of Vitamin D in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome." The Indian Journal of Medical Research 142 (3): 238-40.

30. Fazelian, Siavash, Mohamad H. Rouhani, Sahar Saraf Bank, and Reza Amani. 2017. "Chromium Supplementation and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology: Organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements 42 (July): 92-96.

31. Mikkelsen, Kathleen, Lily Stojanovska, Momir Polenakovic, Marijan Bosevski and Vasso Apostolopoulos. 2017. "Exercise and Mental Health." Maturitas 106 (December): 48-56.

32. Guszkowska, Monika. 2004. "(Effects of Exercise on Anxiety, Depression, and Mood)." Psychiatrie polska 38 (4): 611-20.

33. Harrison, Cheryce L., Catherine B. Lombard, Lisa J. Moran, and Helena J. Teede. 2011. "Exercise Therapy for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review." Human Reproduction Update 17 (2): 171-83.

34. Patten, Rhiannon K., Russell A. Boyle, Trine Moholdt, Ida Kiel, William G. Hopkins, Cheryce L. Harrison, and Nigel K. Stepto. 2020. "Exercise Interventions in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Frontiers in Physiology 11 (Juli): 606.

35. Picchi Ramos, Fabiene K., Lúcia Alves da Silva Lara, Gislaine Satyko Kogure, Rafael Costa Silva, Rui Alberto Ferriani, Marcos Felipe Silva de Sá und Rosana Maria dos Reis. 2016. "Lebensqualität bei Frauen mit polyzystischem Ovarialsyndrom nach einem Widerstandstrainingsprogramm." Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia E Obstetrícia / RBGO Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe 38 (07): 340–47.

36. Dapas, Matthew, Frederick T. J. Lin, Girish N. Nadkarni, Ryan Sisk, Richard S. Legro, Margrit Urbanek, M. Geoffrey Hayes und Andrea Dunaif. 2020. "Eindeutige Subtypen des polyzystischen Ovarialsyndroms mit neuartigen genetischen Assoziationen: Eine unüberwachte, phänotypische Clustering-Analyse." PLoS Medizin 17 (6): e1003132.

37. Toosy, Sehar, Ravinder Sodi und Joseph M. Pappachan. 2018. "Mageres polyzystisches Ovarialsyndrom (PCOS): Ein evidenzbasierter praktischer Ansatz." Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders 17 (2): 277–85.

Wenn Sie Trainer sind oder es werden möchten…

Zu lernen, wie man Klienten, Patienten, Freunde oder Familienmitglieder durch gesunde Ernährung und Veränderungen des Lebensstils coacht – auf eine Weise, die auf ihren einzigartigen Körper, ihre Vorlieben und Umstände zugeschnitten ist – ist sowohl eine Kunst als auch eine Wissenschaft.

Wenn Sie mehr über beides erfahren möchten, beachten Sie die Precision Nutrition Level 1-Zertifizierung.